By Uchenna Ekwo

In spite of efforts to improve Africa’s image in the world, some governments in the continent continue to introduce ridiculous policies better suited for the 19th century. The latest is Uganda that has recently approved legislation that makes it difficult for three or more persons to hold discussions in public.

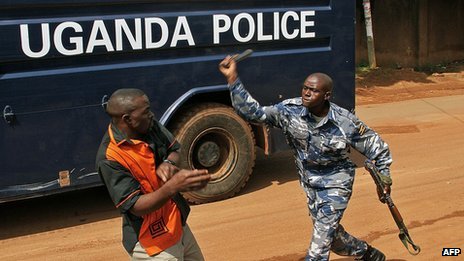

Under the Public Order Management Act, police approval will now be required if three or more people want to gather publicly to discuss political issues. To put this in context, a family of 3 or more who are on vacation at the east African country could be arrested for discussing politics in Kampala. Imagine, friends gathered at Times Square in New York being forbidden from discussing political activities except with the express permission of the police!

What happens to churches and mosques in the country? Perhaps, the law will restrict preaching by priests, pastors and Imams to the Bible and Koran because using the pulpit to comment on political developments with police permit may attract punishment under the new law.

By Uganda’s new law, citizens’ participation in the political process is under threat. Besides, the law is an affront to citizens’ right to free expression. According to Amnesty International the law is part of a pattern of repression, pointing to the closure of two newspapers and two radio stations in the country in three months ago for reporting on an alleged government plot to assassinate opposition MPs.

To say the least, the law is a bad one and ill conceived. It is a major setback to freedom of speech, expression, and assembly- important democratic tenets. And most importantly, the law is a contradiction to the country’s constitution that clearly protects rights to free speech and peaceful assembly. The legislative process that led to the enactment of Public Order Management Act is symptomatic of all that is wrong with democracy in emerging countries where excessive deference to the executive by the other branches of government results in misrule, malfeasance, and malcontent.

There are lots of imponderables in assessing the reasonableness of the law under discussion: How can a democratic society grow when oxygen is taken off the citizens who are supposed to contribute ideas that will propel progress?

If such a law existed prior to 1986 when the current Uganda President, Yoweri Museveni fought the government of Milton Obote from the bush, would it have been possible for him to hold meetings with his group that toppled the government?

Could this be a response to avert a similar uprising that occurred in Egypt in 2011?

Without equivocation, one is inclined to believe that Museveni, who took power by force in 1986, is jittery that his long reign may well end like the erstwhile Egyptian President, Hosni Mubarak, hence his increasingly use of the security forces to intimidate the opposition and civic groups critical of his long rule.

The wind of change that is sweeping across North Africa is almost certain to occur in Sub-Saharan Africa. The likes of Museveni, Mugabe and dictators south of Sahara must be apprehensive about the possibilities of people’s revolution.

The latest action of the Museveni regime against his own people is a desperate move and a sign that his long rule is coming to an end. As the saying goes those whom the gods want to destroy they first make them mad. But as smart as Museveni has been, muscling public opinion and public debates in a world where the public sphere has expanded beyond physical space cannot be sustained for too long. Today, Ugandans can hold virtual meetings via the Internet or mobile phones and even connect their fellow country men and women in the Diaspora. Anyone can communicate with anyone, anytime, anyhow using any platform in what Eric Schmidt, chairman of Google called the “interconnected estate”.

It really defies understanding why some contemporary leaders are still trapped in the 19th century mindset believing as Museveni does that they can control the people against their will. Pharaoh existed in Egypt with awesome powers, so did Hosni Mubarak and they succeeded in diminishing dissent. Uganda’s new law against public gathering to discuss political developments in their country is reminiscent of decrees under previous dictators such as Ghadafi, Saddam Hussein, and Ben Ali. But where are they today? They have all been flushed by the people, the ultimate repository of power in all societies.

The specter of Egypt looms large in Uganda and perhaps the rest of sub-Saharan Africa that is yet to experience its own political hurricane. If history is any guide, civilization started in Egypt and spread across other lands; it may well be that other African countries will soon embrace the lessons in citizens’ resistance to oppression from the same Egypt.

Hopefully, this new assault on human freedom will be a galvanizing force to uproot not only dictators but also dictatorship in all its forms in Uganda and other parts of Africa where similar cultures pervade the public psyche.

Dr. Uchenna Ekwo wrote from New York email: uchenna@167.99.239.142