How Jola Ogunlusi and His Contemporaries Shaped the Profession in Africa’s Largest Democracy

By Sani Zorro

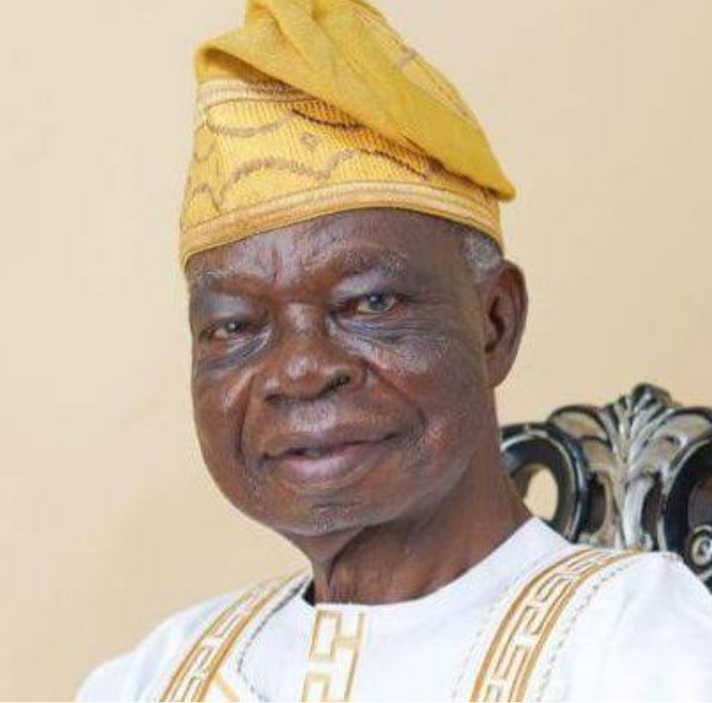

The history of Nigerian journalism is punctuated by defining moments and transformative figures whose leadership and mentorship laid the foundation for the profession’s enduring relevance. Among these figures, the late Comrade Jola Ogunlusi stands out as a towering presence during what many regard as the golden era of Nigerian journalism.

Ogunlusi, who passed away in April 2025 at the age of 91, was more than a journalist—he was a unionist, mentor, and defender of press freedom 1. As National Secretary of the Nigeria Union of Journalists (NUJ), he played a pivotal role in unifying a fragmented media landscape during a politically volatile period in the 1980s. His leadership helped steer the NUJ through factional divides, enabling it to confront threats to press freedom and advocate for journalists’ welfare 2.

This era, spanning the late 1970s through the 1990s, was marked by a surge in investigative reporting, editorial independence, and the rise of journalists as public intellectuals. Ogunlusi and his peers—many of whom were trained in both local and international institutions—mentored a generation of reporters who would go on to shape public discourse and challenge authoritarian regimes.

The golden era also coincided with Nigeria’s post-independence media expansion. Newspapers like The Guardian, Punch, and The Concord became platforms for robust political commentary and civic engagement. Journalists such as Dele Giwa, Ray Ekpu, and Bayo Onanuga emerged as fearless voices, often at great personal risk.

According to historical accounts, Nigerian journalism evolved from its colonial roots—where it served as a tool of missionary and colonial propaganda—into a powerful force for nationalism and democracy 3. The post-independence period saw the press become a watchdog, holding power to account and amplifying marginalized voices.

In 1983, I was elected Secretary of the Nigeria Union of Journalists (NUJ), Kano State Council, following a highly contested biennial congress. This marked a turning point in my unionist journey, paving the way for broader leadership roles in media unionism across Nigeria and beyond. My path was shaped by several mentors, notably the distinguished Comrade Jola Ogunlusi—NUJ’s revered administrator and a staunch advocate for press freedom.

That year was politically charged, with shifting alliances influencing not only national politics but also union dynamics. NUJ elections reflected these tensions, dividing journalists between federal and state media affiliations. Supporters of Aminu Kano’s faction of the defunct People’s Redemption Party (PRP) aligned with federal media candidates, while those loyal to Abubakar Rimi’s faction backed correspondents from southern-based outlets operating in Kano.

Ultimately, Nasir Zaharaddeen of NTA was elected Chairman, while I, then a reporter with Triumph Newspapers, became Secretary. During the campaign, I was labeled—fairly or not—as a militant supporter of Rimi’s administration and an advocate of the Lagos-Ibadan media axis.

Following the elections, strategic realignments ensued. Some of us sought to reconnect with the Adedojah/Ogunlusi faction of NUJ, which had split from the Ralph Igwa/Joseph Angulu group in 1980. By 1983, NUJ’s internal divisions mirrored national political fractures, with each faction claiming regional dominance.

At our first general meeting, the NUJ Kano State Council resolved to disengage from the Ralph Igwa faction and align with the mainstream Adedojah group, led by Comrade Ogunlusi as National Secretary. Recognizing our shared vision, Ogunlusi entrusted me with a mission to northern states to foster unity and strengthen the union’s capacity to defend press freedom and protect journalists.

Under Ogunlusi’s leadership, the NUJ national secretariat had already demonstrated its commitment to press freedom—most notably in its defense of NTA reporter Vera Ifudu, who faced Senate pressure to retract a report on the alleged disappearance of ₦2.8 billion in oil revenue.

As a courageous journalist, Vera defied a Senate resolution, upholding the core principles and ethics of the profession. Similarly, the late Prince Tony Momoh, then Editor of Daily Times, resisted pressure from the Second Republic Senate to reveal his sources—another landmark defense of press freedom.

In these pivotal cases, Jola Ogunlusi stood firm against institutional attempts to silence the media. The National Secretariat retained the late Barrister Fola Akinrinsola—himself a former Punch reporter—who successfully defended many of the union’s cases pro bono. Jola was known for his persistent press releases highlighting attacks on press freedom and for leveraging the Nigeria Labour Congress and international journalist organizations to amplify the Nigerian media’s plight.

With Kano setting the pace, state councils gradually abandoned the Ralph Igwa faction and aligned with Adedojah’s purposeful leadership, supported by the National Secretariat. This shift culminated in a unified meeting of all state councils in Minna in 1985, where I was elected National Ex-Officio Officer.

The year 1984 was particularly challenging. The military ousted the civilian government on January 1 and soon suspended the 1979 Constitution, including its pro-media provisions in Sections 22, 48, and 49. The enactment of Decree No. 4 and the July 4 sentencing of Guardian journalists: Tunde Thompson and Nduka Irabor marked a low point for press freedom. Historically, Nigerian media had played a central role in the decolonization process and enjoyed relative freedom—even under colonial rule.

Decree No. 4 was a moral and political aberration, penalizing journalists for embarrassing public officials regardless of truth or accuracy. Though The Guardian retained Chief Rotimi Williams, Nigeria’s most prominent lawyer, to defend its staff, it was the Nigeria Union of Journalists (NUJ) that led the charge in defending media freedom, job security, and journalists’ welfare. The union’s mobilization—both domestically and internationally—was unprecedented and drew global condemnation of the regime.

Much of this resistance was driven by Comrade Ogunlusi, whose fearless commitment to the union inspired many of us to serve the cause of justice. In state-owned media, military interference led to abrupt changes in leadership and editorial direction, often resulting in staff victimization. These challenges compelled some of us to confront the situation, even at great personal risk. The same oppressive atmosphere extended to federally controlled media houses.

In the wake of military intervention in Nigeria, newly appointed chief executives initiated a sweeping crackdown on workers across all cadres, culminating in a massive retrenchment exercise nationwide. The military, upon assuming power, had announced the removal of all political appointees in ministries, departments, and agencies at both state and federal levels.

Despite limited resources—personnel, funding, and organizational infrastructure—the national secretariat of the Nigeria Union of Journalists (NUJ), under the leadership of Comrade Ogunlusi, responded vigorously to this onslaught. Through the declaration of trade disputes, legal actions, and other available tools, the union defended the employment security and welfare of journalists, as well as the broader principles of freedom of expression and media independence.

It is for these bold and strategic interventions that I regard our late boss and mentor as the true Torchbearer of the NUJ’s golden era—an era when journalists conducted their professional engagements with honor, pride, and the confidence that the union stood firmly behind them.

A Legacy of Leadership and Mentorship

I was not the only disciple, admirer, or mentee of Comrade Ogunlusi. Among his many protégés and colleagues were the late Segun Obilana, Labour Editor of The Punch and pioneer president of the Labour Writers Association of Nigeria (LAWAN); Seyi Adekeye, Group Labour Editor of the defunct Concord Press; Owei Lakemfa of The Guardian and later Vanguard; Adebayo Bodunrin, formerly of The Punch and Vanguard; and Salisu Nuhu Mohammed, formerly of The Triumph and the Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC).

Others included Ladipo Lawal, who succeeded me in office; Dapo Aderinola of The Daily Times; Kayode Komolafe, formerly of The Guardian and Concord, now Deputy Managing Director at ThisDay; his wife, Funmi Komolafe, formerly of Vanguard; Akanimo Samson; Bassy Ekpo Bassy, a former Deputy President of the NUJ; Bolaji Kareem; the late Keji Daudu; Adio Saka; Tony Masha; Festus Iyamu of The Daily Times; Lanre Ogundipe; Muhammed Sani Potiskum; Uchenna Ekwo; Margaret Essien; Joel Ighure; Richard Akinnola; Ipalibo Karibi-Botoye; Augustine Wikinaka; and countless other colleagues and comrades, both living and departed.

Custodian of the Union’s Integrity

As custodian of the union’s records and documents, Comrade Ogunlusi maintained files on every elected officer at both state and national levels. No election was recognized without his validation, and he was therefore—rightly or wrongly—often seen as a kingmaker. He co-signed the press cards of all journalists alongside Prince Tony Momoh, then chairman of the union’s accreditation committee, and maintained the register of all practicing journalists in Nigeria. In this vantage position, he exercised enormous, though often discretionary, power.

A Man of His Time, A Man Ahead of His Time

The 1980s marked the height of the Cold War between the socialist and capitalist ideological blocs. In Nigeria, trade unions sympathetic to Western capitalist countries aligned with the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU), while those inclined toward socialist ideals affiliated with the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU). The Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC), under the leadership of Comrade Hassan Sunmonu, and the majority of its 43 affiliate unions, leaned toward the former. However, the NUJ, as a critical member of the NLC, received scholarships, exchange visits, and solidarity from WFTU-aligned unions.

I personally benefited from training programs in Bulgaria, Hungary, and Cuba between 1983 and 1985—experiences that broadened my worldview and deepened my commitment to the union cause.

Beyond Academic Laurels

In earlier times, a university degree was not a prerequisite for practicing journalism—whether in Nigeria or the United Kingdom. Many of the finest editors, writers, cartoonists, and broadcasters held only diplomas from regional polytechnics, yet they practiced journalism of a quality that remains unmatched today.

Comrade Ogunlusi was one such figure. Though he did not boast of academic laurels, he blazed a trail that few NUJ officers—from pioneer president Mobolaji Odunewu and Secretary General Olu Oyesanya to present-day leaders—have matched. His book, “NUJ: A History of the Nigerian Press”, published by John West Publishing Company, remains the only comprehensive attempt to document the union’s contributions to nation-building from 1955 through the 1980s.

A Life of Continued Service

In 1990, Comrade Ogunlusi retired from the union’s service at the National Executive Council (NEC) meeting in Calabar, Cross River State, with full benefits. Yet, retirement did not mark the end of his service. During my tenure as National President (1990–1994), he was regularly invited to union events and continued to serve in a fatherly, advisory capacity.

Although I had the honor of lowering the casket of George Anyakora, Comrade Ogunlusi’s successor, in his native Anambra State, I deeply regret that I could not participate in the funeral rites of our hero due to health challenges.

Comrade Ogunlusi was more than a unionist; he was a visionary, a mentor, and a guardian of journalistic integrity. His legacy lives on in the countless journalists he inspired and the institutions he helped to build.

Today, as Nigerian journalism navigates the challenges of digital disruption, misinformation, and economic precarity, the legacy of Ogunlusi and his contemporaries remains instructive. Their commitment to ethical journalism, mentorship, and institutional development offers a blueprint for rebuilding trust in the media and nurturing the next generation of journalists.

Alhaji Sani Zoro, President Emeritus of the Nigeria Union of Journalists and former member of Nigeria’s lower c legislative chamber – the House of Representatives